Yoshitoshi Tsukioka. Bushu Rokugo funawatashi no zu. Ukiyo-e, 22,5×15,9 cm. 1868.

In the evening of January 3, 1868, a party of Satsuma clan samurai stormed the gates of Kyōto-gosho, the imperial residence in Kyōto. The samurai eventually make their way inside. Once inside, they searched the palace for Tennō (Heavenly Emperor) Meiji (1852-1912).[1] When the samurai discovered Meiji, they compelled him to defy the shōgun (army leader who battles barbarians), Tokugawa Yoshinobu (1837-1913), and declare the restoration of imperial sovereignty.[2]

But Yoshinobu refused to give in, and thus the Boshin War (1868-1869) began. On January 8, he declared the restoration unlawful and declared it null and invalid. Following that, he began to prepare for war. On the 25th of January, he dispatched a 15,000-man army to Kyōto to put down the insurgents.[3] However, the army would never arrive here because it was defeated at Toba-Fushimi by the 5,000-strong Satsuma and Chōshū army.[4] Following this defeat, Satsuma-Chōshū forces marched on Edo, and Yoshinobu opted to surrender without further fighting on April 4th. Remnants fought until they were decisively defeated at the Battle of Hakodate on June 27, 1869, but the Tokugawa shogunate’s 265-year rule ended on April 4, 1869. Thus, the Meiji era (1868-1912) began on this date, and for the first time in 500 years, a Tennō governed without a shōgun.[5]

The Meiji Restoration was a revolutionary rupture with the past. The Meiji era is distinguished by the desire to fortify and enhance the country.[6] This is the period when efforts are being made to strengthen Japan’s military and economic capabilities.[7] This strategy, known as fukoku kyōhei, was primarily concerned with subduing local authorities, restructuring the central government, and constructing a new administrative machinery for the entire nation.[8]

The definition of a revolution, according to Encyclopaedia Britannica, is ‘Revolution, in the social and political sciences, a major, sudden and therefore typically violent change in government and in related associations and structures.’[9] Thus the Meiji Restoration is a revolution. There are several approaches to revolutions, which frequently depend on distinct viewpoints or beliefs regarding revolutions.

The first is Karl Marx’s well-known theory (1818-1883). Marx’s theory revolves around class struggle, ‘[…] in a word, oppressor and oppressed constantly confronted each other, waged a continuous, now hidden, now open struggle, a struggle that ended every time either in a revolutionary reconstruction of society in general, or in the common ruin of the warring classes.’[10]

Second, there is the theory of Charles Tilly, a sociologist, political scientist, and historian (1929-2008). Tilly’s theory focuses on political power, ‘Consider a revolution as a forced transfer of power over a state in which at least two different groups of contenders make incompatible claims to control the state, and a significant portion of the population under the jurisdiction of the state, rests in the claim of the other.’[11]

Marx and Tilly’s views vary, therefore this essay will examine the restoration of Tennō Meiji’s during January 1868 form both of these theoretical perspectives.

Utagawa Hiroshige III. Yokohama Kaigan Jōkisha Zu. Ukiyo-e, 25.4 x 12.3 cm. 1872.

Chapter I the Meiji Restoration through the eyes of Karl Marx

‘The history of all past societies consisted of the development of class antagonism, antagonism that took different forms in different eras.’[12] This was also true in nineteenth-century Japan. This antagonism eventually explodes in 1868. At that moment, one socioeconomic class is supplanting another, and feudalism is giving way to capitalism. Historical Materialism is the name given to this dialectic.

Class struggle

Marx claims that all history can be reduced to a battle between oppressor and oppressed, or a class struggle. Every state has a degree of social rank, and during a revolution, the upper rank is replaced with a lower rank. Following the revolution, the new ruling class will rebuild society, resulting in new classes, new circumstances, and new tyranny.[13]

The above also applies to the 1868 Meiji Restoration. During this revolution, two classes vie for control, and the successful class finally restructures society. During the Meiji Restoration, two factions of daimyō (title for lord) fought each other: the challengers are the Tozama (outside daimy), and the established order is the Shinpan (relatives of the shōgun).[14]

The establishment was led by a shōgun from the Tokugawa clan. After the battle of Sekigahara (1600), the Tokugawa clan dominated over Japan. Following this triumph, the Shogun imposed a four-class system and froze the social order. The four classes were samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants. The samurai class was split further into subclasses. The first was the daimyō, which was split into three groups: Shinpan, fundai (Tokugawa friends), and Tozama.[15]

Tokugawa Japan was an agricultural society and all these daimyō had their own domain and there they produced rice. During the Tokugawa shogunate period, the shōgun produced 7 million koku (1 koku = 4.96 bushels) of the 30 million koku in rice, or rice equivalents, produced across the country.[16] Rice was a means of payment at the time and thus the source of wealth in Japan.[17] There was also a hierarchy depending on the amount of rice a daimyō produced, thus rice served as both a form of payment and a status symbol.[18]

As a result, the Tokugawa clan was the most land-owning clan, and land was the primary source of income.[19] Therefore this is thus a feudal form of production, distinguished by a ‘[…] exploitative relationship between landowners and subordinate peasants.’[20]

Their opponents, the Tozama, were clans that had not been affiliated with the Tokugawa prior to the battle of Sekigahara (1600), and were hence considered misfits of the Tokugawa shogunate.[21] Satsuma and Chōshū clans were among the Tozama. When the capitalist United States of America disrupted Japan’s 250-year isolationist sakoku period in 1853, exposing Japan to the global market, these two clans had efficiently adapted.[22] Between the opening of Japan in 1853 and the Meiji Restoration in 1868, they restructured their economies, strengthening their financial condition.[23] Most clans, including the Tokugawa clan, were unable to transform their domains and lagged behind.[24]

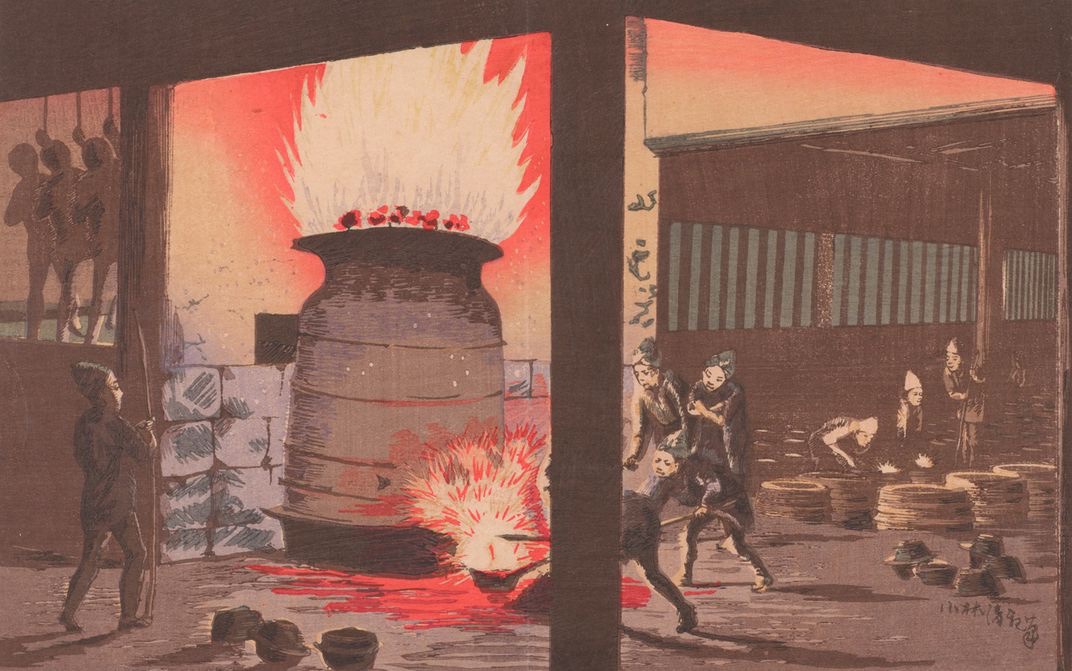

Furthermore, the Satsuma clan possessed a monopoly in Japan over the profitable sugar manufacturing.[25] The excess from sugar production was invested in production equipment and the procurement of Western technologies. This enabled them to establish tiny industrial complexes equipped with blast furnaces to manufacture glass, cannons, ceramics, and weapons. The production surplus was resold in order to generate a profit for reinvestment. These complexes were run by paid employees, also known as the proletariat.[26]

Both the Satsuma and the Chōshū clan were backed by the industrialized capitalist British empire.[27] As a result, the Satsuma and Chōshū clans might be considered a proto-bourgeoisie. Not only did they get money from land, but also through industry and the selling of commodities.

In 1866, the Satsuma and Chōshū clans joined forces to resist the shōgun. This eventually resulted in a conflict between the two groups, in which the existing order was vanquished and replaced.[28]This occurred when the proto-bourgeoisie seized control of the Kyōto-gosho, the imperial mansion in Kyōto. The storming of the palace elicited a reaction, and the existing feudal system attempted to reverse it. Then the feudal lord was defeated in a fight at Toba-Fushimi by the proto-bourgeoisie.[29] This was possible because the proto-bourgeoisie possessed more sophisticated weaponry. The defeat of the Tokugawa Shogunate at Toba-Fushimi paved the way for Satsuma and Chōshū forces to march towards Edo, the capital of the Tokugawa shogunate. They never took the city, however, since Tokugawa Yoshinobu submitted without a final fight.[30]

The new order

Following the 1868 restoration, members of the Satsuma clan reshape economic policies. They maintain certain aspects of its state-led economic policy, but there is also a general trend toward the free market.[31] They are likewise devoted to utilizing Western practices to increase national prosperity and strength.[32] In 1869, they also abolished the daimy domains known as the han and replaced them with prefectures.[33] Thus, the changes put in place ensure that feudalism is put to rest and that the road is cleared for capitalism.

For the reasons stated above, it is possible to say that there is class conflict since the proto-bourgeoisie of the Satsuma and Chōshū clans fought the feudal lord of the Tokugawa clan. Following this triumph, the Satsuma and Chōshū clans abandoned feudalism in favor of capitalism. That is why, during the Meiji Restoration, one can talk about Historical Materialism.

CHAPTER II the Meiji Restoration through the eyes of Charles Tilly

‘Revolutions resemble traffic jams, which vary widely in form and severity, blend imperceptibly into routine vehicle flows, evolve out of those flows and occur under different conditions for a number of reasons.’[34] It is true, however, that one revolution shares traits with previous. Some causative processes may be recognized, such as the spectacular revelation of a formerly powerful state’s vulnerability and the partial disintegration of existing state powers.[35]

Overall, it is possible to say that every revolution consists of ‘[…] a forced transfer of power over a state in which at least two different groups of contenders make incompatible claims to control the state, and a significant portion of the population under the jurisdiction of the state acquiesces in the claim of the other.’[36] These instances are divided into two parts: a revolutionary circumstance and a revolutionary result.[37] This revolutionary approach also applies to the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Revolutionairy situation

In a revolutionary context, multiple sovereignty arises when two or more blocs establish effective, opposing claims to rule or be the state.[38] This can occur when non-ruling forces organize and seize control of portions of the state. This is accompanied by social support and the establishment’s incapacity to stifle this collaboration.[39]

During the Meiji Restoration, a similar revolutionary situation existed. The establishment was headed by the shōgun of the Tokugawa clan. After the battle of Sekigahara (1600), the Tokugawa clan ruled over Japan. Following this triumph, the shōgun imposed a four-class system and froze the social order. There were samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants among them. The samurai class was further subdivided. The first was the daimyō, which was divided into three groups: Shinpan, fundai (Tokugawa friends), and Tozama.[40]

Their opponents, the Tozama, were clans that had not joined with the Tokugawa prior to the battle of Sekigahara (1600), and were thus considered misfits of the Tokugawa shogunate.[41] The Satsuma and Chōshū clans were among the Tozama.

Both of these non-ruling clans had their own han, or realm. The Chōshū clan’s han encompassed much of southwestern Honshu, while the Satsuma clan’s han encompassed much of Kyūshū and the Ryukyu Islands. For generations, both clans resided and dominated in this region.[42]

It were also these Tozama daumyō’s who took advantage of the instability produced by the United States’ opening of Japan in 1853, since this scenario allowed them to acquire more power in the political arena. They believed that the Tokugawa clan was too weak to stand up to foreign forces.[43] They demonstrated this by planning assaults and instigating revolts. For example, Chōshū was a center for anti-Western and anti-Tokugawa forces. They also attempted to take Kyōto in 1864, but the assault failed, and the Tokugawa conducted a punitive campaign to pacify the insurgents. This pacification was not fully effective, and they quickly recovered.[44]

After regaining control, they concentrated on opening up to Western connections and technology. This appears to be paradoxical because they first took action against the Tokugawa for this reason, but in the end, it is about making selective decisions to build their own state rather than unfettered westernization.[45]

In 1866, the Satsuma and Chōshū clans banded together to oppose the shōgun.[46] Other clans, including the Tosa and Aizu, as well as certain shōgunal administrators and officials, eventually joined the Satsuma and Chōshū alliance.[47] In June 1866, the second pacification attempt to eliminate the Chōshū clan failed due to the Chōshū clan rebuilding its military forces and other daimyō failing to come to the Tokugawa’s help.[48]

This eventually leads to the early morning incident of January 4, 1868, when the Satsuma and Chōshū faction claimed control of Japan. Tennō Meiji was compelled to depose shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu and announce the restoration of imperial sovereignty by Satsuma and Chōshū clan samurai.[49]

As a result, there were two factions: the Tokugawa clan’s establishment and the Satsuma and Chōshū clans’ challenging party. The Tokugawa clan does not pacify the Satsuma and Chōshū clans. As a result, the Satsuma and Chōshū clans seize control of Japan. This resulted in multiple sovereignty.

Revolutionairy results

When power shifts from the establishment to the challenger, a revolution occurs. This generally occurs after the revolutionary faction obtains armed forces and after the establishment’s armed forces and authority over the state machinery are neutralized by members of the revolutionary faction.[50]

This is likewise true of the Meiji Restoration. Following the Satsuma and Chōshū alliance’s claim to power, shōgun Yoshinobu intervenes, leaving Kyōto and settling in Ōsaka castle. He planned a strategy here, and on January the 8th, he proclaimed the Restoration null and void.[51] On January 25, he dispatched a 15,000-man army to Kyōto.[52] The army, would never arrive. Between the 27th and 31st of January, this army was beaten at Toba-Fushimi by the 5,000-strong Satsuma and Chōshū army.[53]

Following this defeat, the Satsuma-Chōshū forces began their advance on Edo. On April 4, when this army was 100 kilometers from Edo, shōgun Yoshinobu opted to surrender without further battle. Later that month, on the 7th, he promulgated the Oath of the Five Articles. This commitment would serve as the foundation for Japan’s future. Tennō Meiji then boarded a palanquin and traveled with his household from Kyto to the new capital called Tokyō. Tenn Meiji did not write the oath, but rather a group of samurai who were significant figures in the Meiji Restoration.[54]

Conclusion

For the reasons stated above, it may be claimed that there is a forced transfer of power over a state with at least two distinct groups of competitors make irreconcilable claims to govern the state. So you have a revolutionary situation in which the Satsuma-Chōshū coalition challenged the Tokugawa clan’s established rule. They eventually seized control of Japan via the Tennō, with the help of their own han, the Tosa clan, the Aizu clan, and certain Tokugawa administrators. Furthermore, the Tokugawa clan failed to pacify the challengers three times. As a result, there is also the issue of multiple sovereignty.

Then it is also possible to say that this revolutionary condition resulted in a revolutionary outcome. Satsuma-Chōshū troops defeated the Tokugawa army at Toba-Fushimi. The Satsuma-Chōshū clans then seized Edo, the seat of Tokugawa authority. Following this, the Satsuma-Chōshū faction restructures and reorients society.

Shōkōsai Kunihiro Hitsu. 毛理嶋山官軍大勝利之図. Ukiyo-e, 37 x 148 cm. 1868.

[1] Charles Holcombe, A History of East Asia; From the origens of civilization to the twenty-first century (Cambridge (UK) 2017) 244-245.

[2] Ibid., 159 en 244-245.

[3] Ibid., 159; Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan: Meiji and his world, 1852–1912 (Manhattan 2002) 125.

[4] Mikiso Hane and Louis G. Perez, Modern Japan: a historical survey (United States 2012) 86.

[5] Keene, Emperor of Japan, 16.

[6] Hane and Perez, Modern Japan, 84.

[7] Ibid., 84.

[8] Ibid., 85.

[9] Encyclopaedia Britannica, ‘Revolution’ (edition 14-3-2021), https://www.britannica.com/topic/revolution-politics (14-3-2021).

[10] Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848) 14.

[11] Charles Tilly, European Revolutions, 1492-1992 (Oxford (UK) and Cambridge (USA) 1993) 8.

[12] Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party, 26.

[13] Ibid., 14.

[14] Hane and Perez, Modern Japan, 17.

[15] Ibid., 17.

[16] Ibid., 18.

[17] Ibid., 41-42.

[18] David L. Howell, “Proto-Industrial Origins of Japanese Capitalism.” The Journal of Asian Studies 51 (1992) 2, 269-86 there 280.

[19] Hane and Perez, Modern Japan, 18.

[20] Howell, “Proto-Industrial Origins of Japanese Capitalism”, 270.

[21] Hane and Perez, Modern Japan, 17.

[22] Ibid., 84.

[23] Holcombe, A History of East Asia, 243.

[24]Charles L. Yates, “Saigō Takamori in the Emergence of Meiji Japan”, Modern Asian Studies 28 (1994) 3, 449-474 there 456-457.

[25] Holcombe, A History of East Asia, 243.

[26] J. Sagers, Origins of Japanese Wealth and Power: Reconciling Confucianism and Capitalism, 1830-1885 (New York 2006), 68-70.

[27] George M. Wilson, “Plots and Motives in Japan’s Meiji Restoration”, Comparative Studies in Society and History 25 (1983) 3, 407-27 there 413.

[28] Holcombe, A History of East Asia, 243.

[29] Ibidem 159; Keene, Emperor of Japan, 125.

[30] Holcombe, A History of East Asia, 159.

[31] Sagers, Origins of Japanese Wealth and Power, 91.

[32]John Breen, “The Imperial Oath of April 1868: Ritual, Politics, and Power in the Restoration” Monumenta Nipponica 51 (1996) 4, 407-29 there 426.

[33] Sagers, Origins of Japanese Wealth and Power, 92.

[34] Tilly, European Revolutions, 7.

[35] Ibid., 8.

[36] Ibid., 8.

[37] Ibid., 10.

[38] Ibid., 10.

[39] Ibid., 10.

[40] Hane and Perez, Modern Japan, 17.

[41] Ibid., 17.

[42] Ibid., 72-74.

[43] Ibid., 72-74.

[44] Ibid., 75.

[45] Ibid., 75-76.

[46] Holcombe, A History of East Asia, 243.

[47] Hane and Perez, Modern Japan, 76.

[48] Ibid., 76-77.

[49] Holcombe, A History of East Asia, 159 en 244-245.

[50] Tilly, European Revolutions, 14.

[51] Keene, Emperor of Japan, 123-124.

[52] Holcombe, A History of East Asia, 159; Keene, Emperor of Japan, 125.

[53] Hane and Perez, Modern Japan, 86.

[54] Keene, Emperor of Japan, 137-139.

Copyright © 2021 Studentlifehistorian.com