“In heaven there is paradise. On earth, Suzhou and Hangzhou.” — Marco Polo

In 1125 AD the Jurchen invaded Song China and captured the capital at Kaifeng. After this loss, the Song dynasty moved southwards and reestablished itself in Hangzhou. From this city the Song would continued to rule for another 150 year (Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279)). Poets after 1127 reflected on this shift, by remarking that the new capital at Hangzhou has manifoldly increased the inherited splendor of the lost capital at Kaifeng (De Pee 179-181)

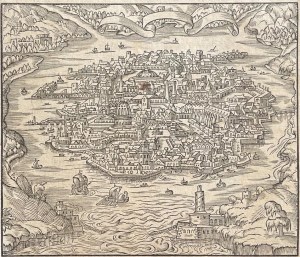

The above map of Hangzhou is called Xuntien alias Quinzay, and it was originally included in the book Theatrum Urbium Celebriorum, which was published in Amsterdam in 1657. Maps are always influenced by the worldview and intention of their creators (Black 29-58). This means that the map of Hangzhou is a product of its time, and more specifically said, the vision of its creator Johannes Janssonius (1588-1664). This fact is the reason why the central question of this essay is “What elements influenced Johannes Janssonius’ portrayal of Hangzhou?”

This question is related to how maps and imagination work together, but it is also connected to how maps are a product of it’s creator. To effectively address this question, this essay will discuss the following three elements. The first element revolves around an exploration of the genre to which Janssonius’ map belongs. The second element is an analysis of the visual aspects of the map of Hangzhou, during this the focus will lay on the representations of urban landscapes and architectural features. The third element is an inquiry into possible sources of inspiration that were available to Janssonius. By employing this framework, this essay aims to uncover the underlying factors that influenced Janssonius’ portrayal of Hangzhou, shedding light on the cultural, artistic, and geographical influences that shaped his perception of the city.

Hangzhou according to Johannes Janssonius

Johannes Janssonius was a Dutch printer, bookseller, and publisher based in Amsterdam during the 17th century. He married the daughter of fellow cartographer Jodocus Hondius (1563-1612). Together with his brother-in-law, he founded one of Europe’s largest publishing companies. Jansonnius published numerous multivolume atlases and worked to improve the Mercator-Hondius atlas. Some of the maps he created were not only based on existing copper plates from other publishers, such as Georg Braun’s (1541-1622) and Frans Hogenberg’s (1535-1590) city books, but also on renowned cartographer Lodovico Guicciardini’s (1521-1589) Description de Touts les Pays Bas. Janssonius and his business also frequently collaborated with other printers, publishers, booksellers, engravers, and cartographers in Amsterdam and the rest of Europe (“Biography Johannes Janssonius (1588-1664)”).

Janssonius depiction of Hangzhou reflects the broader cultural and cartographic trends of the 17th century. An important visual aspect of the map is the certain way the map portrays the city. When this map is compared with maps of other cities from the same time period, certain similarities in visual representations and cartographic techniques can be discovered. An analysis of this will create a broader understanding of Janssonius’ map within the context of cartographic practices of the time.

The 1657 map of Hangzho that was printed in Amsterdam provides a bird’s-eye view of Hangzhou. This was a well established topographical tradition in the Low Countries. According to scholar Hartzer Nguyen, this genre was the most popular of the two basic compositional types of topographic illustration of that time. The genre provided basic information about the cities outline and it’s infrastructure and major buildings. She also emphasizes that these maps were usually designed to impress the viewer of the city’s wealth, prosperity, and dominance (Hartzer Nguyen 11-14). An interesting aspect of this visual representation of a city through a birds eye perspective creates a map that is too unclear and ambiguous for accurate navigation, therefore the map may have acted as an decorative item (Van Egmond).

Civitates Orbis Terrarum, Liber Primus. Antwerp, Gilles van den Rade, 1575

A Ilha e Cidade de Goa Metropolitana da India E Partes Orientais que esta and 15 Graos da Banda da Norte, Arnoldus and Henricus Van Langren, 1596, source University Utrecht.

Another important and relatively well known work in this genre is Braun and Hogenberg’s city atlas, Civitates Orbis Terrarum, published in 1572, which represents towns and cities in a similar manner (Braun & Hogenberg). It also turns out to be the case that Amsterdam was in this atlas and that the atlas was also available in the Netherlands (Braun & Hogenberg). This atlas was not the only city atlas in circulation, during the 17th century at least 6 city atlasses were available in the Low Countries (Braun & Hogenberg). Next to that, singular birds eye perspective maps of cities also existed. One example is A Ilha e Cidade de Goa Metropolitana da India E Partes Orientais que esta and 15 Graos da Banda da Norte. This map of Goa was created in Amsterdam in 1596 by the mapmakers Arnoldus (1580-1644) and Henricus (1574-1648) Van Langren. As a result, it is clear that Janssonius was able to draw inspiration from a variety of sources for his map of Hangzhou, as there were numerous city atlases and city maps in circulation that depicted cities from a bird’s-eye perspective, which was a well-established cartographic theme.

A supportive argument for the claim that he followed the well established theme is that the focus in Johannes Janssonius map of Xuntien alias Quinzay shows similarities with other bird eye view maps such as those of Braun & Hogenberg. One example would be the foregrounding of big buildings. The accent on big structures is also something present in the city maps in Civitates orbis terrarum (Braun & Hogenberg). A possible interpretation of this could be that this focus is a way of showing wealth and richness.

This interpretation is possible if you take in consideration that big building projects in the 13th century required a vast control about resources and manpower. Sinologist Jacques Gernet wrote in his book, Daily life in China, on the eve of the Mongol invasion, that Hangzou was the richest and most populous city of the 13th century. The city’s grand buildings demonstrated its luxury and wealth. Throughout the city, numerous grand palaces, temples, and monasteries were constructed. Furthermore, sources explicitly state that the southern part of the city, around Mount Phoenix, was reserved for the wealthy and this area was adorned with mansions, pavilions, pagodas, and groves (Gernet 24–29 and 54-55). As a result, focusing on large structures emphasizes wealth and power. However, it isn’t exact clear in Janssonius map what the big buildings are supposed to resemble. The big visible and distinctive buildings in the map are a round golden domed structure, several big towers with spires, several arched walls that look like roman aqueducts, multiple long stretched multi stored buildings, and other big buildings with blue rooftops. Nothing on the map resembles a pagoda, a Chinese temple, a Chinese monastery, mount phoenix or a grove. Therefore the by Gernet described landmarks that show wealth are not present in the map. Nevertheless, the map contains other big structures that represent power and wealth, but these elements are not present in the real Hangzhou.

The display of power is also being displayed on the foreground of the map. The map shows two fortresses at the place where a body of water flows into the lake wherein the city lies. Between these two fortresses a big anti ship chain is portrayed. Therefore, this image shows the defensive capabilities of the city. The military power is further emphasized by the size of the towers, when compared to the ship next to it, the tower is two and a halve times it’s size. Therefore the map shows the significance, power and splendor of Hangzhou as the former imperial capital of the Song Dynasty. However, this is done by showing rather European looking defensive structures. The city itself is for example build in a star like shape, alongside the waterside there are outward projected angular bastions, which were key features of European military architecture of the 17th century.

Some of the inspiration for the map can be traced back to Marco Polo. According to map scholar Marco Caboara, the city plan is partly based on Marco Polo’s (1254-1324) description of Hangzhou from The Travels (ca. 1300). This is one of the reasons why the map highlights a large amount of bridges, an extensive network of canals, and a large lake (Caboara). Gernet writes that these canals served as the main commercial arteries of the city, and the clear emphasis on them signals that they stand as a symbol for wealth and commerce. This is further emphasized by the portrayal of economic activity in the shape of shipping, because the map shows many barges and boats alongside the canals (Gernet 38-40).

However, Jansonnius representation of Hangzhou also differs significantly from Marco Polo’s account. This is for example visible in shape of the city. During the late Song and early Yuan dynasty, Hangzhou was a rectangular shape city situated between a lake and a river, rather than a circular city in the center of a lake (Gernet 24). The map’s creator also left out elements for which Hangzhou was known, such as mountains, pavilions, urban gardens, lush natural landscapes, great parks, and the great West Lake (De Pee 179-185). Furthermore, the Imperial Way, which was the city’s main road connecting the palace to the city gates, is missing, despite the fact that Marco Polo specifically mentioned and described it in his work (Gernet 40-41). Marco Polo also emphasised that the city was filled with bustling markets and numerous bathouses, but Jansonnius also did not portray them on the map (Polo 231-239). Then there is the case of the imperial palace. Marco Polo writes that the palace was enormous. He says that was ten miles long and enclosed by walls with battlements. The palace consisted of 1000 rooms and 20 great halls. It also had gardens with lakes and orchards, but a marvelous palace like this is not visable on Janssonius map (Polo 239, 243-244).

Another source of inspiration for Janssonius’ map of Hangzhou, is the work of French missionary Andre Thevet (1516-1590). Thevat’s map named Chine Hángzhōu Quinsaï gravure de 1575 par Andre Thevet (1504-1592) closely resembles Janssonius’ Xuntien alias Quinzay, albeit being older and less detailed. This map was initially included in a book from 1575 named La Cosmographie Universelle, and it includes several more fictitious maps based on Marco Polo’s narrative.

Therefore Janssonius map is well embedded in broader cultural and cartographic trends of the 17th century. Next to that the map displays Hangzhou in a typical European style and tries to highlight power and splendor that befits a former imperial capital city. Furthermore it has been shown that the information used by Janssonius not only stemms from Marco Polo’s account, and from another map produced by Andre Thevat, but also from himself. It is plausible that Janssonius read Marco Polo’s account and used his interpretative abilities to translate a written account into a visual image. The map is also mainly a creation of pure imagination, because many elements such as the palace and the key visual landmarks that were described by Marco Polo, are not present on the map.

Conclusion

it can be argued that the way Johannes Janssonius depicted Hangzhou on his map reflects broader 17th-century cultural and cartographic trends. It can also be argued that his visual representation was influenced by a variety of sources as well as his own interpretive abilities. This essay examined three key elements that influenced Janssonius’ depiction of Hangzhou. These elements centered on genre exploration, visual analysis, and sources of inspiration.

In the end, it has been established that Janssonius’ map of Hangzhou belongs to the bird’s-eye view genre. This was a popular topographical tradition in the Low Countries during the 17th century. The genre aimed to impress viewers with the city’s wealth, prosperity, and dominance by emphasizing significant buildings and key infrastructure. Janssonius map, just like the other maps in that genre, emphasizes large structures in order to convey wealth and power. However, the map deviates significantly from historical reality by depicting a European-looking city. The map also omits key landmarks described in historical sources used as inspiration. According to scholars, Janssonius drew inspiration from a variety of sources, including Marco Polo’s writings and Andre Thevet maps.

Finally, this essay demonstrated that the map represents both artistic interpretation and the dominant European cartography style of the time. Janssonius’ depiction of Hangzhou is a combination of facts, artistic conventions, and cultural perceptions. The mix of these components emphasizes the city’s power and splendor as a previous imperial capital while simultaneously demonstrating the constraints and creative liberties inherent in 17th-century mapmaking.

Bibliography

- “Biography Johannes Janssonius (1588-1664).” Gallerease, gallerease.com/en/artists/johannes-janssonius__3d0f396bd464.

- BLACK, Jeremy. Maps and Politics. REAKTION BOOKS, 1998.

- Braun, Georg & Frans Hogenberg, Civitates orbis terrarum. Keulen, [Peter von Brachel, et al.], 1572-1618. Zes delen in twee banden. 2º (Utrecht UB, T fol 212 Rar).

- Caboara, Marco. “Translations; Xvntien Alias Qvinzay [Xuntien, Also Known as Quinzay].” China In Maps 500 Years of Evolving Images, https://library.hkust.edu.hk/china-in-maps/exhibits/translations.

- Cohane, Ondine. “The Poetry of Hangzhou.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 8 Apr. 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/04/10/travel/10next-hangzhou-china.html.

- de Pee, Christian. “Nature’s Capital: The City as Garden in The Splendid Scenery of the Capital (Ducheng Jisheng, 1235).” Senses of the City: Perceptions of Hangzhou and Southern Song China, 1127–1279, edited by Christian de Pee et al., The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2017, pp. 179–204. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2n7r8r.12.

- Gernet, Jacques. Daily Life in China: On the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250-1276. Stanford University Press, 1995.

- Hartzer Nguyen, Kristina. “The Made Landscape: City and Country in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Prints.” Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin, vol. 1, no. 1, 1992, pp. 1–47. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4301455.

- Jansson, Jan. Xvntien alias Qvinzay [Xuntien, also known as Quinzay]. Rare & Special E-Zone, HKUST Library, https://lbezone.hkust.edu.hk/bib/b538783.

- Polo, Marco, and Henry Yule. The Travels of Marco Polo: The Illustrated Edition. Sterling Pub., 2012.

- Van Egmond, Marco, “Wereldsteden van de 16de eeuw.” Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht, https://www.uu.nl/bijzondere-collecties/collecties/kaarten-en-atlassen/stadsplattegronden/stedenatlas-van-braun-hogenberg.

- “Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279): Essay: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Department of Asian Art, 1 Jan. 2001, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ssong/hd_ssong.htm.

Copyright © 2024 Studentlifehistorian.com